Are Britons falling out of love with booze?

Nick TriggleHealth correspondent

Britain has always been known as a nation that loves a tipple. But the latest Office for National Statistics lifestyle survey suggests this may be coming to an end.

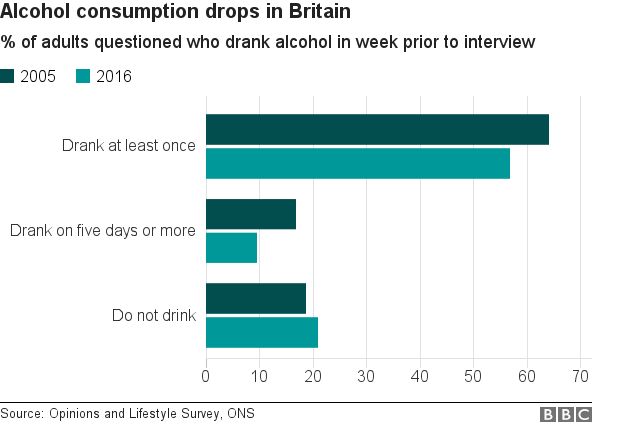

The 2016 poll of nearly 8,000 Britons found just under 60% had had a drink in the past week - the lowest rate since the survey began in 2005.

Of those who had not had a drink, half were teetotallers.

Are people really cutting back?

One of the problems with the ONS survey is that it is based on people's own recollections - and it is well known that we are terrible for underestimating our drinking.

But there is evidence to be found elsewhere that the fall in alcohol consumption is real.

The findings chime with a much longer running source - the British Beer and Pub Association's data on the sales of pure alcohol.

It shows in the early 1950s alcohol consumption per head was below four litres of pure alcohol a year - the equivalent of about 140 pints of beer.

In the following decades, that climbed, particularly during the 1960s and 1970s.

By 2004, it had peaked, topping 9.5 litres.

Since then though, it has fallen and is now back under eight litres.

The young are not big drinkers

There are a variety of reasons that have been put forward for this trend - and to understand them you need to look at who is drinking and who is not.

And this is where the ONS data is particularly useful.

Perhaps surprisingly, young people are not the biggest drinkers - in fact, they are among the age groups least likely to have consumed alcohol in the past week.

Fewer than half of people aged 16 to 24 had had a drink, compared with nearly two-thirds of those aged 45 to 64.

Various reasons have been put forward for this - from the recession, changes in technology and globalisation making the work place more competitive for young people to the rise of social media allowing online socialising rather than meeting for a quick drink in the pub.

Immigration is also likely to be a factor - drinking rates tend to be lower in areas with high levels of ethnic diversity.

Baby boomers are the ones at risk

But that, of course, suggests problem drinking is still a problem among certain age groups.

A major part of the increase in drinking from the 1960s onwards has been driven by the rise in boozing at home - twice as much alcohol is now bought from shops than is purchased in bars, pubs and restaurants.

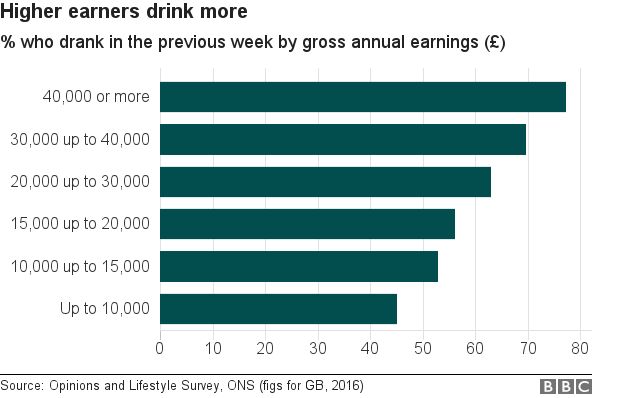

This form of alcohol consumption is more common in the older age groups and explains why the most frequent drinkers are the middle-aged, particularly those among high income groups.

Drinkers earning £40,000 or more are 50% more likely to have drunk in the past week, compared with those on £10,000 to £15,000.

A common justification put forward is that these people are drinking responsibly.

That is certainly true in terms of anti-social behaviour, but the evidence is pretty damning when it comes to their own health.

A third of the men aged 45 to 64 and a quarter of the women had been binge drinking in the past week, the ONS survey showed.

Dr Tony Rao, co-chairman of the older people's substance misuse working group at the Royal College of Psychiatrists, believes these figures should act as a "wake-up call" to the drinking habits of the baby boomers.

He points out that problem drinking in older age groups is a real threat, with alcohol-related hospital admissions and mental health problems on the rise.

He says: "Alcohol abuse is not a young person problem.

"It is a problem in older age groups, and that's not going to go away."

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-39785742

Reply With Quote

Reply With Quote

Social Networking Bookmarks